One of the most researched and validated theories of volunteer motivation is that functional motives drive the volunteers willingness to join and continue the volunteer activity. Scholars argue that certain pre-exiting needs must be met in order for volunteers to start and stay.

One of the most researched and validated theories of volunteer motivation is that functional motives drive the volunteers willingness to join and continue the volunteer activity. Scholars argue that certain pre-exiting needs must be met in order for volunteers to start and stay.

This theory represents a major finding in the field that has been validated over the years with numerous studies and through the use of a Volunteer Functions Inventory (VFI) survey questionnaire and index.

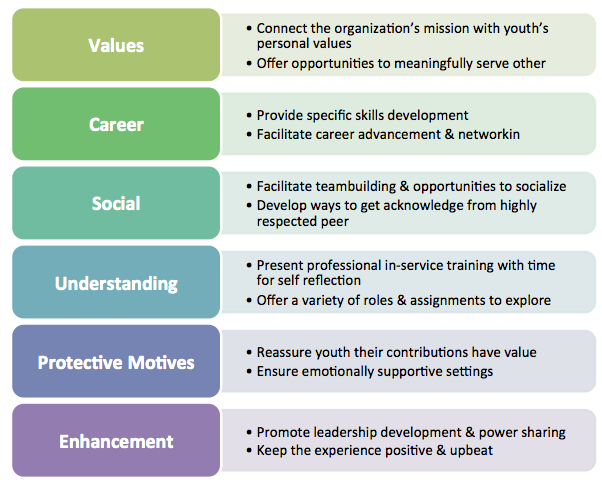

In short, volunteers are more likely to be satisfied and stay with and organization when the experience matches their (often unspoken) needs, which fall into the following categories, regardless of age, culture, background, socio-economic status, etc.:

• Value – to act upon important personal values related to altruistic and humanitarian concerns for others

• Understanding – to learn or exercise knowledge, skills use skills that may otherwise remain unused

• Enhancement – to promote psychological development

• Career – to obtain career-related experience

• Social – to strengthen or create social relationships and manage concerns over social rewards and punishments

• Protective – to reduce negative feelings or personal problems

Although the VFI provides a comprehensive map of the functions volunteering generally serves, Clary and Snyder (1999) point out that different volunteers pursue different goals at different times throughout their lives, and the same volunteer may have more than one important motivation.

Adult vs. Youth Volunteer Motivation

Youth motivation to volunteer has been found to be similar to that of older volunteers, and common themes included helping others, social interaction and recognition. Contrary to popular stereotypes of youth as self involved, youth volunteerism is motivated both by ‘self-oriented and other-oriented motivations,’ but they maintain the commitment for the basis of other-oriented motivations (Marta & Pozzi, 2008).

Not surprising, some motivations are more important in youth volunteering, such as socialization to pro-social behavior, self-actualization, and peer pressure (de Guzman, 2007). In addition, youth volunteers form close bonds with their peers. In one study, Haski-Leventhal, et al. (2008) found “No less than 80% of the youth volunteers said that other youth volunteers were their closest friends.” Only 22% of adult volunteers developed close relationships with fellow volunteers.

Youth Volunteer Motivation: Action Steps

For youth volunteer involvement, these motivations offer a way to design programs that meet volunteers’ needs, effectively design volunteer recruitment messages, and assess whether existing volunteer needs are being met. All can lead to better volunteer retention outcomes. If you hope to diversify your volunteer corps and bring on more youth, consider which of the following you might realistically try.

What Do You Think?

What tactics have you tried to engage youth and young adult volunteers? Have they worked? Tell us in the comments!