How to Skyrocket Your Team’s Success Using Volunteer Mentors

On our blog, we’ve shared some of the distinct advantages of volunteer teams; today, we want to expand on ways peer-to-peer volunteer mentors can expand your team’s skills and knowledge.

Mentoring doesn’t just help volunteers, it can help staff save time by cultivating independent, thoughtful volunteer leaders. Volunteer mentoring, driven by peer learning, can be an effective bridge between the classroom and the workplace without more effort on the part of paid staff. Through mentor-mentee collaboration, volunteer mentors can learn both explicit skills (like knowing the steps in a process) and implicit or tacit skills (like critical thinking and problem-solving).

On the surface, mentoring seems like a simple strategy with simple results, but that couldn’t be further from the truth. Mentoring increases learning retention, builds trust, and deepens volunteer engagement.

Volunteer Mentoring is a Talent Management Tool

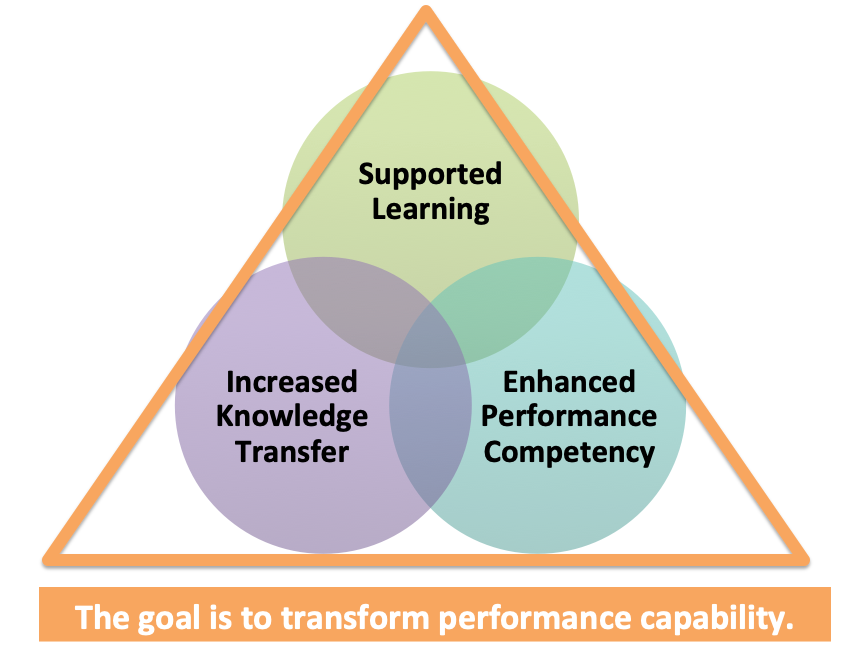

Mentoring is a talent management strategy that facilitates learning, knowledge transfer, and enhanced performance competency. The goal is behavior change that leads to acceptable (or better – exceptional) performance levels on the job.

Mentoring replicates the expertise, wisdom, and skills of professionals (in this case, volunteers) in the heads and hands of their co-workers. It uses the right skills at the right time to keep a volunteer workforce prepared, productive, innovative, and competitive.

The Mentoring Trifecta

For mentees, mentoring offers …

- Knowledge sharing that is customized to the individual

- A strong relationship with a resource other than their supervisor

- A way to reinforce knowledge and skills taught in the classroom

- A way to gain confidence in a safe space

- Increased trust in the organization through greater support

For program staff and agencies, mentoring offers …

- A way to quickly and effectively address program needs and learning gaps

- A way to utilize volunteer leaders effectively in a meaningful way

- Higher levels of volunteer proficiency, particularly in direct service environments

- Deeper trust and engagement between new and more seasoned volunteers

What’s more, in the volunteer context, mentoring also adds a social element to learning that resonates well with volunteers who are seeking connection and meaning in their service experiences. And, with higher quality experiences come higher retention rates.

Volunteer Mentoring Models & Types

There are several types of volunteer mentoring models to choose from based on your training and learning needs. With any of the models listed below, conversations can take place in-person, over the phone, or via video chat with little loss of quality.

- Paired (Traditional) Mentoring is focused on providing support in a highly personal, private, or sensitive nature. It is generally issues-based and characterized by high levels of trust and confidentiality. For example, mentors may help a mentee work through a tough interpersonal issue.

- Reverse Mentoring matches those who would more likely be considered mentors, due to their experience or role in the organization, with a less seasoned leader. This is particularly helpful to bring older volunteers up to speed on technology by working with a younger, more adept volunteer. It has also been used by forward-thinking organizational leaders who want a different perspective on how their leadership affects the organization.

- Group Mentoring brings small groups together who are led by a group mentor-facilitator. Groups benefit from hearing challenges and successes and get to learn from diverse peers.

- Situational Mentoring is more about telling than coaching and is focused on providing clutch, just-in-time information so a problem can be overcome quickly. Rather than rely on a small group to offer constant response, some organizations ask mentees to “give back” and act as a mentor once their pressing need has been met.

- Finally, Peer Mentoring involves people at the same hierarchical level in the organization who are matched to offer information, social support, and encouragement. Peers may work in the same or different departments.

Volunteer Mentors Needs Support & Development

Peer-to-peer volunteer mentors is one of the most cost-effective ways to enhance your training program and build volunteer talent and leadership skills. But, it does take a clear plan of action.

Although seasoned volunteers have a mountain of experience and wisdom to share, as mentors they often don’t know where to start or focus their advice for mentees. Because of this, they may be hesitant to answer the call to mentor their peers.

Here are a few areas where they need help:

Where to Start

Volunteer Mentors are often stuck at the beginning. Unless they have mentored someone before, they don’t know how to officially kick off the relationship in the right way, so it is productive and builds trust over time.

Boundaries & Expectations

Volunteer Mentors often think they must be available to mentees at all times and that all subjects are open for discussion. Both mentors and mentees need to understand their roles, their limits, and the expectations on both sides. A formalized mentor program and a written guide for mentors and mentees can go a long way in helping everyone understand goals and roles.

Trust Building as a Focus

Volunteer Mentors often downplay or misunderstand the critical role trust plays in the success of a mentor-mentee relationship. If an atmosphere of mutual trust can’t be forged quickly, then mentors are unlikely to share vulnerabilities which help mentees learn. And, without vulnerability, mentees aren’t likely to admit where they may be struggling.

To build trust, mentors must be open to disclose specific learning experiences that put the mentee on more even footing. They must also consistently honor their commitments to time, schedule, preparation, and follow up. Finally, they must give their mentees their full attention during meetings by asking follow up questions and eliminating distractions (digital or otherwise).

In addition, certain coaching skills should be developed in volunteers before they take on mentoring:

- Active listening

- Asking open-ended, critical thinking questions

- Using a “yes, and” approach to reduce barriers and resistance

- Providing structure and certainty in a conversation

- Self-reflection and mindfulness as a coach

Coaching vs. Telling

Often volunteer mentors believe they must have all of the answers, but this simply isn’t true. Usually, the answers are present in the mentee themselves, and with a few, well-phrased questions, the mentor can help the mentee come to their own conclusions. One of the goals of mentoring is to help the mentee work independently, and by coaching instead of telling, mentors help foster critical thinking skills and confidence in their peers.

In this coaching role, volunteer mentors might …

- Facilitate problem-solving

- Give feedback though guided reflection

- Assist the mentee with goal-setting by asking and listening

But, good mentoring isn’t all asking. There are times where information and encouragement make sense.

For example, mentors might …

- Point out where resources can be found

- Suggest others mentees should meet

- Gently encourage mentees to take on greater challenges

Closing the Relationship

Mentors should not be expected to continue to mentor the same person for an infinite period of time. Each relationship should have a clear set of goals and a beginning, middle, and end. When the mentor and mentee are ready to conclude the relationships, there should be a series of distinct steps including reflection, celebration, and letting go.

If the relationship is successful, mentees will gain skills for the job and may be better prepared to take on a mentor role themselves to serve the next generation of new volunteers. Mentors gain, too, by continuing to build their skills and confidence through practice.

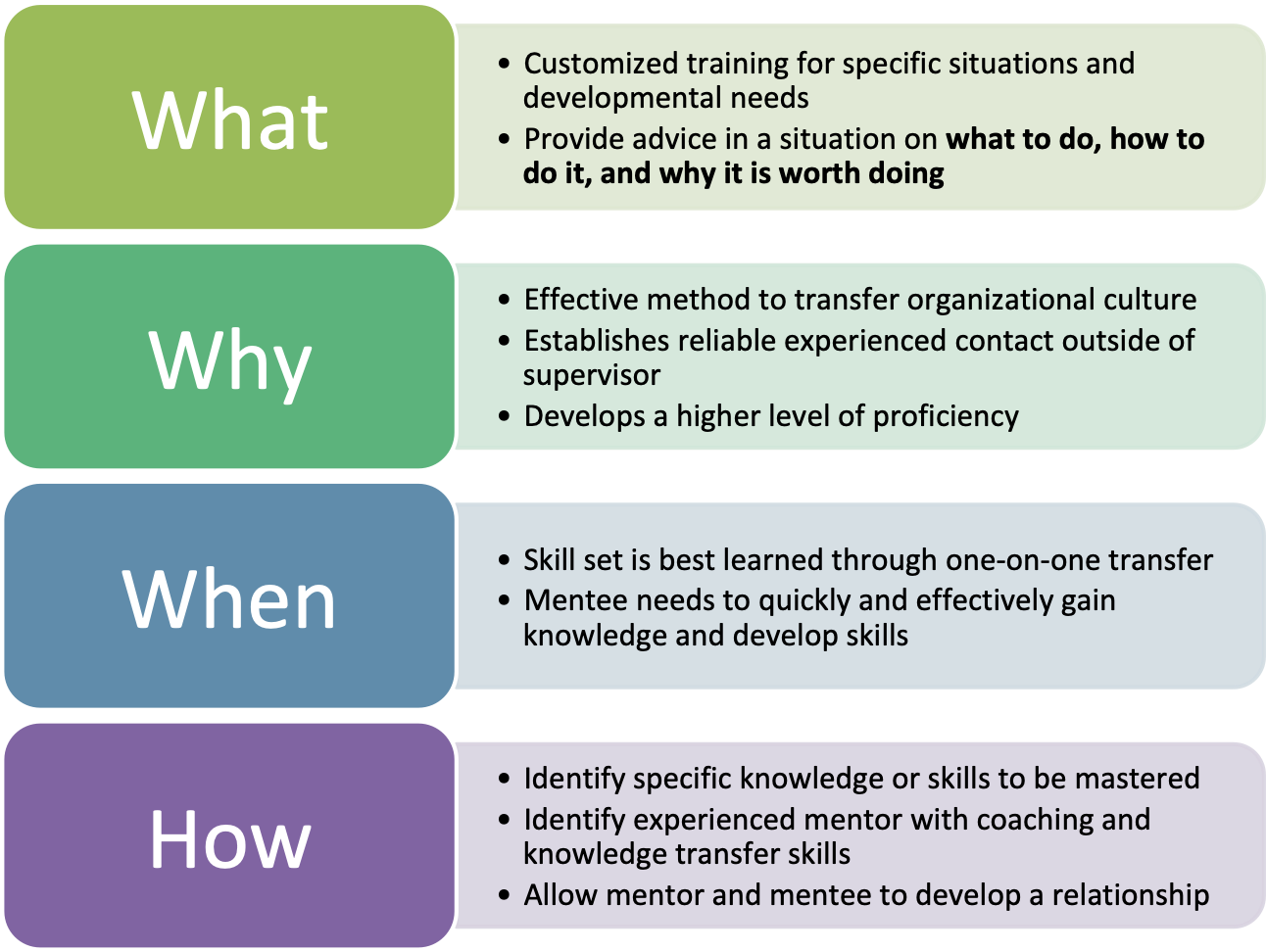

The Basics of Mentoring

6 Steps to Peer Mentoring Success

To set your volunteer peer mentoring program up for success, consider these best practices, uncovered in research report, Workplace Mentoring: An Overview of APQC Best Practices Study Findings published by the American Productivity & Quality Center (APQC).

Although this study was conducted within paid employee programs, the key lessons hold true for volunteer organizations, as well.

1. Define Success

Make sure you are clear about what the volunteer mentor program is set up to achieve in terms of learning outcomes for your organization. If you don’t know where you’re going, chances are you won’t get there. So, define what reward the investment is intended to reap.

APQC outlines four key goals for mentoring:

- The transfer of discipline-specific knowledge — in other words, technical skills for the volunteer role

- Career pathing and counseling — could be helpful for student volunteers, interns, or volunteers seeking leadership roles

- The development of business acumen and soft skills — specifically interpersonal skills and critical thinking

- The dissemination of “insider knowledge” about an organization’s structure, norms, culture, and professional networks — in other words “how we do things around here”

2. Design For a Business Need

Mentoring can’t just be a “feel good.” By designing the program to meet specific business needs (such as speeding up the training process, training for a specific mission-critical competency, developing leaders, or increasing retention rates), you can better evaluate early on whether the program is working and make adjustments to boost its effectiveness.

3. Select Mentors Carefully

Not everyone has the skills and discretion to be a trustworthy mentor. But more importantly, it’s their expertise that will make or break the success of the relationship. Try to select mentors who align with your agency’s standards, really know their stuff, and can relay best practices to new volunteers.

4. Bake Choice Into the Process

Mentors and mentees should have some say in who they choose to be matched with. Allow the pool of volunteer mentors and mentees to meet one another and get input from mentees on preferences to consider when pairing them. While everyone may not get their first choice as a partner, give them some way to prioritize their choices.

5. Set Learning Objectives from the Start

So they are both on the same page, ask volunteer mentors and mentees to discuss what the mentee hopes to learn from the relationship. By taking time to establish a learning agreement, they will be more likely to avoid misunderstanding the purpose of the partnership. In addition, with a written agreement, it will be more clear when they’ve achieved what they set out to do.

6. Share Success Stories

Mentoring is largely a private endeavor, so take steps to elevate the transformations happening behind the scenes with success stories, anecdotal evidence, and satisfaction data. Show everyone how the investment in time and effort pays off for all involved.

Volunteer Peer Mentoring: The Ultimate Learning Accelerator

While you can’t instantly create experience in new volunteers, you can exponentially increase the speed at which they generate wisdom and the critical thinking skills needed for success.

Peer mentoring is a tool that helps you do just that.