Unique Challenges & Solutions for Rural Volunteers

The unique challenges of engaging rural volunteers are well documented. Around the world, leaders of volunteers who work in rural and frontier areas are challenged to find creative solutions to volunteer mobilization when little, if any, infrastructure exists.

And yet, highly engaged rural volunteers can also be important assets for building community cohesion, providing essential and emergency services, and improving the health and well-being of volunteers themselves.

There’s a lot to like about volunteer involvement both as a community development and an emergency response strategy in rural areas. But when it comes to navigating the unique challenges of working in low-population areas, many organizations get stuck.

While every rural community is different and varies by geography, cultural values, and economic base, many face similar challenges, whether they be located in the mountains of West Virginia or the outback of Western Australia.

All have the challenge of engaging the community across the miles.

To help leaders of volunteers and others interested in learning more about rural volunteerism, we break down some of the key barriers to success in this blog post. We also offer up some ideas for managing them.

The Challenges of Rural Volunteer Involvement

Below are some of the most challenging trends for leaders of volunteers in rural areas, along with two key kinds of trends – community trends and volunteering trends.

Community Trends

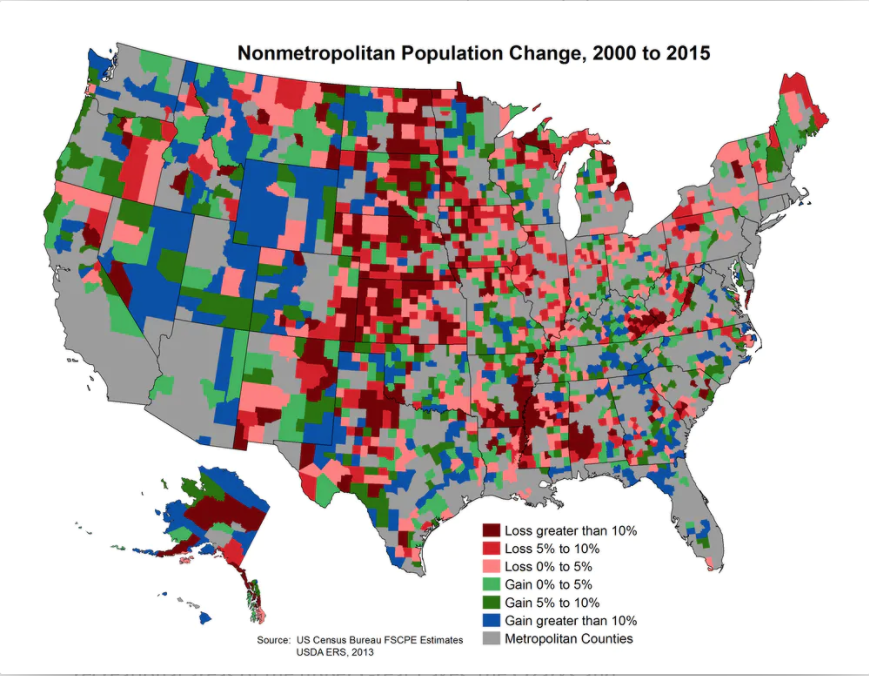

Outmigration – In the US, the rural population grew by only 0.02 percent from 2018 to 2019, a slight increase after six years of population decline, but still well below the urban increase rate of 0.6 percent. That said, not all rural counties have experienced a decline in population and there has been a flattening of the net decrease in rural areas in recent years. Rural counties near urban areas, with beauty and natural resources, that are attractive to retirees, and those that employ immigrants are most often growing.

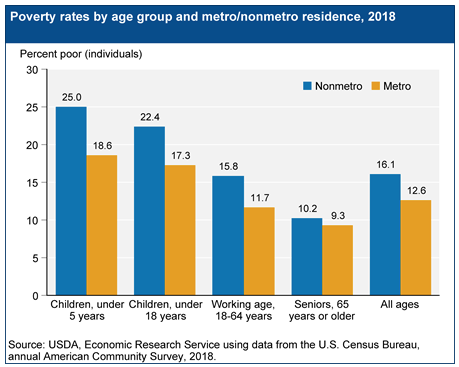

The most common complaint from rural volunteer organizations is the lack of young people to engage. In some rural areas, the outmigration of younger people in search of better jobs to pay for increased student loan debt and other necessities is a common trend. The median age in rural counties is 41.5 years old, more than three years older than their urban counterparts. More than 16 percent of the rural population is over 65, compared to 12.5 percent of the urban population.

Social Isolation – According to the National Conference on Citizenship, since 1960, the percent of households with one person has increased by 114.5 percent, reaching 28.1 percent in 2016. In addition, nearly 35 percent of survey respondents in the US reported feeling lonely at least some of the time.

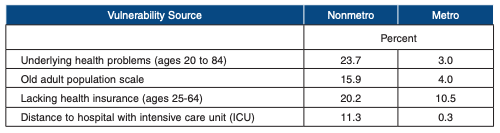

Over 10,000 Americans turn 65 years old each day, and 1 in 4 of these seniors live in rural areas and small towns. In rural areas, social isolation – defined by a lack of relationships or infrequent social contact – is exacerbated by inadequate access to health care, a lack of age-friendly community events or activities, limited transportation, and higher rates of poverty.

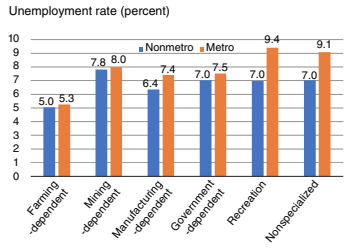

Poverty – Rural counties have added jobs over the past decade but at less than half the rate of urban counties. From 2018 to 2019 rural counties experienced a 0.6 percent growth in jobs compared with 1.4 percent in urban counties.

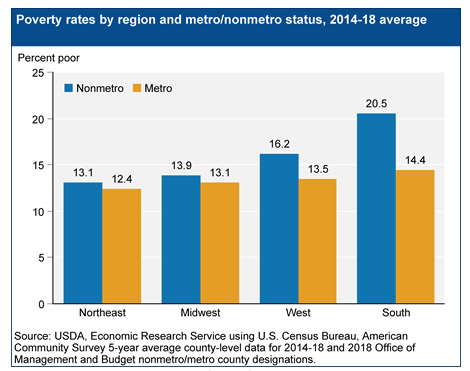

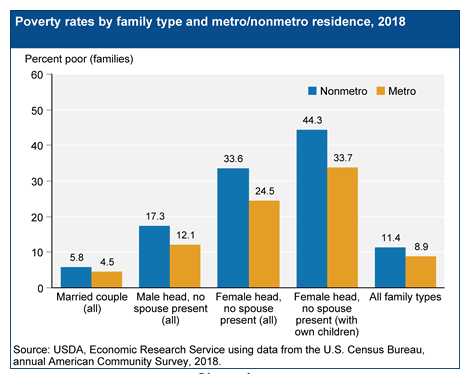

Rural poverty rates dropped from a 2013 rate of 18.4 percent to 16.1 percent in 2018, still well above the urban rate of 12.6 percent. Regionally, nearly 84 percent of persistent poverty counties are in the rural South. For an interactive map of poverty in the US, go here.

Reduced Nonprofit & Government Services – Lack of rural infrastructure, including hospitals and public schools, has been a continuing crisis, impacting the well-being of rural residents. Philanthropic trendwatchers have also noted a precipitous decline in non-governmental support for charities and community organizations in rural areas.

In addition, while rates of illicit drug use are higher in urban areas, as of 2015 the rural rate of drug overdose death rates (17.0 percent) surpassed the metropolitan rate (16.2 percent). The epidemic has created a ripple effect on families, with grandparents and other family members stepping in to help raise children as well as an increase in foster care placements.

As budgets are squeezed, and community crisis goes unabated, essential community programming is needed more than ever. And with shrinking resources for nonprofit employee hires, there is an increasing need for volunteer-driven solutions.

Lack of Broadband Internet Access – Globally, only 59 percent of the population has access to the internet, with 86 percent of the developed world online. Mobile is the most important channel, accounting for 91 percent of total internet users. In the US, rural areas have a disproportionate share of challenges with access. In 2018, approximately 80 percent of the 24 million American households without reliable, affordable high-speed internet were in rural areas.

Volunteering Trends

As the community goes, so too does volunteerism. The community trends noted above no doubt have an impact on volunteering rates and who is available to volunteer.

Scholars and practitioners have noted the following trends in rural volunteerism:

Aging Out of Older Volunteers – As active seniors age in place, they are transitioning from volunteer service provider to nonprofit service recipient. These transitions are not always easy for volunteers, who prefer to be self-reliant. In addition, this represents a “brain drain” for nonprofits that cannot easily replace the intellectual capital, wisdom, and experience of long-term volunteers.

In our annual Volunteer Management Progress Report, we see consistent trends of recruitment and replacement of volunteers as the biggest challenge reported by volunteer organizations.

Volunteer Burnout – Similarly, volunteer turnover is exacerbated by fatigue and burnout in overextended rural volunteers. Due to a lack of new talent, existing community leaders are tapped to take on increased responsibility, which is often unstainable.

While we have posted tips for reducing burnout in volunteers and employees, the fact remains that when there aren’t enough volunteers to manage the tasks at hand – and when volunteers are also managing home and kinship care responsibilities – volunteer well-being and satisfaction may suffer. The result is higher vacancies and reduce rural volunteer retention rates.

Informal Volunteering – Thought leaders have noted the prevalence of an uptick in episodic volunteering for over a decade. For busy volunteers, and those with health issues, the flexibility of event, spontaneous, and one-off service is appealing.

Historically, rural volunteering is also more often characterized by informal, neighbor helping neighbor activities. With the lack of infrastructure and perhaps greater levels of community trust than in urban contexts, rural volunteering is both a necessity and part of what it means to be a good neighbor.

While research has shown that shorter commute times correlate with higher volunteering rates, it’s not clear how physical distance may impact rural volunteering. Because of the informality of rural philanthropy and service, it’s also believed that volunteering rates are chronically under-reported and under-represented in rural communities.

With both community challenges and real barriers to rural volunteerism, it may first appear that attempting to change this reality is impossible.

But there are significant ways that volunteerism can act as a solution to community issues in rural areas on a multitude of levels.

Solutions for Rural Volunteer Challenges

Working to overcome barriers to rural volunteer involvement and participation may not be easy, but it may be well worth the struggle. Below are some solutions to ease the journey, including new ways that scholars are thinking about the value and function of volunteerism in rural areas, as well as suggested rural volunteer engagement and retention tactics.

New Scholarly Thinking

In recent years, social scientists and thought leaders have begun to rethink how volunteerism functions in rural environments.

Volunteer-led services can be created as a support for community resilience, helping combat the rural challenges noted above with direct community action.

Volunteerism is viewed by some as a way to tap the latent community capital that already exists in rural communities. In addition, low-income volunteers are viewed as assets, rather than burdens and bring four key types of valuable “capital” to the table:

- Social Capital – The value of social networks, bonding similar people and bridging between diverse people, with norms of reciprocity.

- Human Capital – The economic value of a worker’s experience and skills, including education, training, intelligence, skills, health, as well as “soft skills” such as loyalty and compassion.

- Cultural Capital – The group-based consciousness, identity, history, and tradition that can be deployed for the development of both individual and group capabilities.

- Political Capital – The resources and power built through relationships, trust, goodwill, and influence used to ensure the responsiveness and accountability of the government and its representatives.

All four of these asset types are already inherent in each volunteer, at various levels, but can also be developed, grown, and strengthened through community volunteerism to benefit the individual and the whole.

Scholars and thought leaders have also written about the potential of volunteerism as an avenue to achieve multi-level wins for rural communities.

As a community development strategy, grassroots to grass tops rural volunteer organizing activities can surface projects that are meaningful and relevant to a local hometown. While many view community development as something that happens overseas, as community members here at home rural volunteers may be the best equipped to identify and solve local problems.

When supported by a nonprofit with mutual goals, local volunteers can amplify what they can achieve by tapping the resources and infrastructure that an organization can bring to the table.

Because of its documented health benefits, volunteerism can be viewed as a public health intervention, both to improve the health of volunteers but also to improve the lives of those they educate and assist.

Along these lines, volunteerism is also used as a youth development activity, helping young people around the world become empowered agents of change. Through service-learning programs and youth-driven models, teens, and young adults both contribute to organizational and community growth and learn valuable skills that are related to their coursework, making it a triple win for nonprofits, students, and educational institutions.

Similarly, volunteerism can become a vital rural employee development program for companies in areas where few local professional and leadership development opportunities exist. Rural corporate volunteering programs can help businesses reach goals by developing their people and building community goodwill simultaneously.

But community engagement initiatives aren’t limited to the corporate world alone. Small businesses in rural communities also participate in supporting local volunteer organizations and events and experience gains as well.

Rural Volunteer Engagement and Retention Activities

When it comes to rural volunteer involvement, traditional volunteer human resources management practices may not be as effective. It takes creativity and a special attunement to local needs to get traction. Below are a few ideas to get started.

Partnering Directly with Communities – Volunteer projects can help grow community leaders through community-centric program development and contextually-relevant volunteer opportunities. This means that volunteers help decide the direction of new programming and help make improvements to existing programming so that it better meets the needs of their communities.

These benefit the volunteer as well as the community. For example, volunteer-driven programs that are well designed can improve rural health outcomes on both the micro and macro level.

Community Mapping – When infrastructure is limited, the Asset Based Community Development (ABCD) model may be an effective volunteer engagement model. As such, mapping the community to identify assets and places to extend invitations into the process is a great start in engaging the community and locating potential volunteers.

Community mapping, or participatory asset mapping, is a group process to identify infrastructure assets and resources within a defined area (people, physical structures, organizations, and institutions) that can be utilized to develop and support community projects. For example, rural schools (even those that have closed) and health centers can be infrastructure assets for rural volunteer meetings, training, and gatherings.

When the community is engaged from the beginning in pinpointing community problems, and mapping what resources can help solve them, the more likely they will be to stay engaged in the project until the end.

Digital Literacy Development – Working online, rural volunteers can have a major impact on an organization’s progress if they are given the tools and guidance needed for successful virtual volunteerism.

While worries remain about issues with internet connectivity, the good news is that options for broadband internet access continue to grow, with nearly every county in the United States with at least one fixed broadband provider (to check your state or county, go here for an interactive map).

In addition, satellite-based internet services are on the horizon. What remains to be seen is whether rural communities will find them affordable and worth learning to use.

Sources of Rural Volunteer-Ready People

Finally, in terms of volunteer engagement, there are three particular groups that are more likely to be engaged in rural volunteering. For organizations that need volunteers quickly, these “low-hanging fruit” are the types of volunteers to reach out to first.

Youth and Students – When designed correctly, volunteerism helps the community and the student achieve educational outcomes. In the community mapping process, be sure to include a list of all of the educational institutions in your area – both secondary and post-secondary – that may be interested in service-learning partnerships.

Seniors and Retirees – While many bemoan the outmigration and “brain drain” of local communities, others have noted a rural “brain gain” of people aged 30-49 and 50-64 who tend to make the move to rural areas for a simpler pace of life, safety, security, and lower housing costs. The lived experiences of mid-life to older people are assets that rural organizations can put to use.

At the same time, it’s important to consider how to mitigate barriers to volunteering for older people. Currently, 13 percent of rural seniors have no car, and 40 percent of all rural residents live in counties without public transportation. That said, carpooling and virtual volunteerism may offer solutions to transportation woes and, at the same time, decrease social isolation for volunteers.

Workplace-sponsored Volunteers – Corporate, small business, education, and public sector employees are all high potentials for employee volunteer programs.

And, while many see rural areas as primarily an agricultural base, the fact is that farmers are not the most workers in rural America. In the US, less than 5% of the rural workforce works in agriculture. Indeed, across rural America, it is services (professional, health, retail, social, tourism), manufacturing, energy, and government that are the primary employers and increasingly important drivers of rural economies.

Organizations that regularly come into contact with these groups can be found in many communities and unearthed through the community mapping process.